What is the Current State of the Coal Industry in the US?

By James Murray

May 23, 2020 - When Murray Energy filed for bankruptcy in October 2019, it became the eighth US coal producer to do so in the space of 12 months, as the price of the fuel fell by 38% from a year earlier.

One of the latest casualties is Longview Power, which declared itself bankrupt on 14 April. Its financial troubles indicate the “increasingly dire state” of the country’s coal industry, according to IEEFA.

Longview’s primary asset is the 700-megawatt (MW) Longview Power Plant in Appalachian coal country near the city of Morgantown, West Virginia.

The IEEFA claims the plant has “much more going for it than most coal-fired plants in the US”, of which many are “far older, less efficient, and pay more to get their coal delivered”.

As it looks to shore up its long-term future, the bankrupt firm is now shifting its focus towards building a 1.2GW combined-cycle gas-fired facility and a 70MW utility-scale solar farm.

As for coal mines, following a drop in demand for the fuel, the number of active sites has plummeted from 1,435 in 2008 to 671 mines in 2017, according to the EIA.

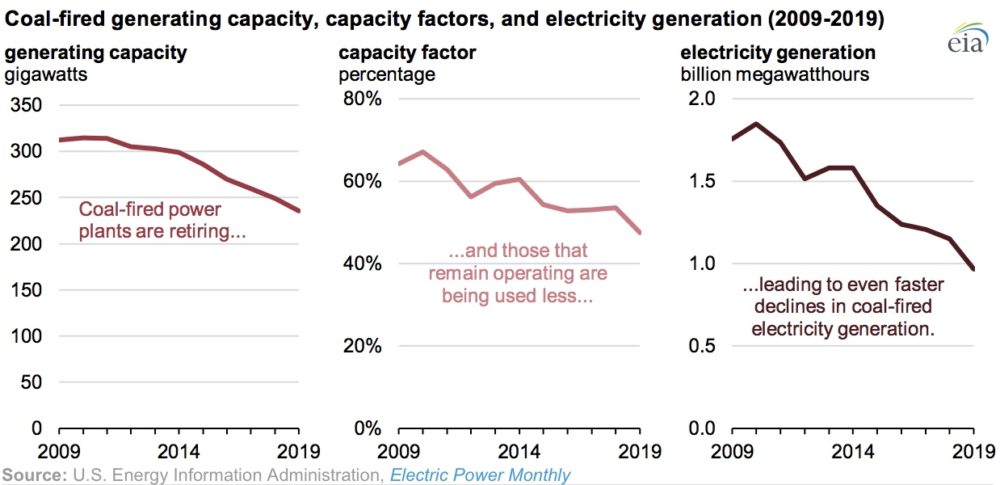

Coal-fired generation capacity dropped dramatically between 2009 and 2019

Credit: EIA

The EIA’s data also shows that between 2010 and the first quarter of 2019, US power firms announced the retirement of more than 546 coal-fired power units — representing about 102GW of generating capacity and roughly a third of the coal fleet that was operating in 2010.

While 21 new units have opened across the nation over the past decade, the last of those to come online was the 106MW Spiritwood Industrial Park near Jamestown, North Dakota, in 2014.

But its owner, Great River Energy, announced in May 2020 that the station will be converted from lignite to natural gas in the near future.

The EIA’s analysis also highlights that “coal-fired units that retired after 2015 in the US have generally been larger and younger than the units that retired before 2015”.

It said the US coal units that retired in 2018 had an average capacity of 350MW and an average age of 46 years, compared with an average capacity of 129MW and an average age of 56 years for the coal units that retired in 2015.

Despite Trump’s efforts to revive the industry, more coal-fired plants were shut down in his opening two years in office compared to Obama’s entire first term.

Between 2009 and 2012, 14.9GW of coal power went offline, as opposed to 23.4GW between 2017 and 2018, according to the EIA.

After reaching a peak for shutdowns or conversions under Obama’s leadership in 2015 at 19.3GW, 2019 marked the second-highest year at 15.1GW.

Has the Coal Industry Stabilized Since Trump Came Into Office?

In June 2017, Trump claimed at a rally in Iowa that he had “ended the war on coal” and was “putting the miners back to work”.

While figures from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), the government’s principal fact-finding agency, backed up his claim that 33,000 mining jobs had been created (actual number 32,600) since his inauguration in January that year, it came with a caveat.

That’s because the mining category also included oil, gas extraction, quarrying and non-metallic mineral mining jobs – and just 1,000 of the additions were coal-based.

Then, at an August 2018 rally in Charleston, the president declared to the crowd “we are back – the coal industry is back”.

But in September 2019, Cecil Roberts, president of the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA), said his message to Trump and others running for the presidency in 2020 was that “coal’s not back” and “nobody saved the coal industry”.

He added it was a “harsh reality” that coal-fired plants were closing all over the country.

Not that all blame can be directed at the incumbent of the Oval Office — indeed, Trump may never have been able to truly stem the flow.

The NCC’s Gellici notes four policy factors that have contributed to the closure of plants, many of which she claims were established under Obama’s administration and were either already underway or had been completed by the time Trump came into power:

- Regulatory requirements increasing costs of maintenance and operation

- Regulatory mandates requiring an increasing percentage of intermittent renewable energy (IRE) to be deployed by US utilities

- The EPA’s New Source Review discourages utility investments that would increase emissions in coal power stations

- Preferential treatment for IRE in funding support and regulatory treatment.

The NMA’s Burke believes many people have been either “too quick to dismiss or discount” the impact Trump’s administration has had in “reversing the almost cliff-like negative impact the Obama administration had on coal employment”.

She says employment plummeted from 134,000 in 2008 when Obama took office to 81,000 when he left in 2016 – a near 40% decline.

“In the first several years of this administration, the declines stopped and employment stood at just north of 82,000 for 2018,” she adds.

“Of course, the current situation in the electricity markets stemming from the coronavirus pandemic is one that no one could have anticipated and the long-term impacts are yet to be seen.”

The latest figures from the BLS suggests the nation’s coal-mining employment levels sat at 51,100 in January this year and its preliminary projections for April suggest that total has since tumbled to 43,800 as IEA forecasts suggest energy demand will drop 9% in the US and 6% globally this year.

US Coal Consumption Plunging at the Fastest Rate Since the Eisenhower Era

Plant closures led to the largest decline in American coal consumption since former president Dwight Eisenhower’s era 65 years ago, Bloomberg reported in March.

In 1954, coal usage dropped by 14%, only to rebound by 15% the following year.

Total consumption slumped from 688 million short tonnes (MMst) in 2018 to 596MMst in 2019, according to the EIA — marking a 13% decline.

But the industry shouldn’t expect an Ike-like comeback this time around, with a further 13.3% drop to 516MMst predicted for 2020.

The declining coal consumption dovetails with falling output. The EIA cites the 16% decline in coal generation to 966,000GWh last year — representing the largest ever percentage drop and lowest production level, respectively — to several factors.

“Although lower electricity demand in 2019 was partly responsible for less coal-fired generation, the primary driver was increased output from natural gas-fired plants and wind turbines,” the EIA added in a report published on 11 May.

Natural gas-fired generation reached an all-time high of nearly 1.6 million GWh in 2019, up 8% from 2018. Electricity generation from wind turbines also set a new record, surpassing 300,000 GWh, up 10% from 2018.