Arch Coal at Crossroads in Review

By Dennis Webb

July 17, 2017 - Looking every bit as comfortable in hiking gear as he might be in courtroom attire, attorney Ted Zukoski of the conservation group Earthjustice led a group of environmentalists deep into the Gunnison National Forest east of Paonia, Colorado on a sunny late-June day.

With Matt Reed of High County Conservation Advocates helping lead the way, the hikers passed a no-motor-vehicles sign as they forayed into the Sunset Roadless Area abutting the edge of the West Elk Wilderness at the base of 12,700-foot Mount Gunnison. They passed below a beaver pond, observed bear scat and trees marked by bear claws, enjoyed abundant wildflowers, and braved a banner crop of mosquitoes thanks to plentiful breeding waters after a bountiful winter snowmelt. They strode below giant aspens and conifers that David Inouye, a retired University of Maryland biology professor along for the outing, guesstimated might respectively be about 100 and 300 years old.

Bushwhacking above the scalloped cliffs of a slumplike geological formation on the scantest of trails, the group finally reached a flat grove of aspen at the top of a hill.

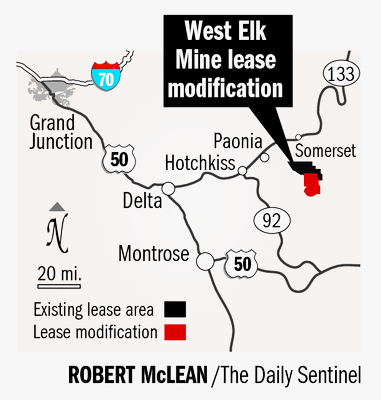

It’s on this spot, Zukoski pronounced, that Arch Coal wants to build a temporary pad for one of a number of exploratory wells it hopes to drill on some 1,700 acres of the roadless area if it’s able to obtain coal lease modifications from the federal government for its West Elk Mine.

This particular pad would be reached by building a temporary road with eight switchbacks, Zukoski said.

“This whole forest is going to have a road going zing, zing, zing, zing, zing,” he said, emphasizing each turn in the slashing route that road-builders would carve.

This secluded spot where Zukoski and Reed stood, so hard to reach now even by foot, is ground zero for environmentalists opposing Arch Coal’s proposal.

Said Reed, “This is the heart of the roadless area and the heart of the aspen forest and the heart of the big spruce and this is … right where a pad and a road will go.”

For them, what’s at stake was visible from an overlook just a few hundred feet away at the hikers’ lunch spot. At the bottom of the hill, a drill rig was operating where Arch Coal already mines underground. The company drills methane vent wells to keep miners safe from explosions during its longwall mining operations.

Ultimately, Arch Coal envisions potentially building more than six miles of temporary roads and 48 pads to drill methane wells across the 1,700 acres it hopes to lease. It already has developed dozens of such wells elsewhere in the area, including at least 89 within two miles of the proposed lease modification area, most or all of them on national forest.

Climate Considerations

Besides marring pristine forest, the expansion would provide for more venting into the atmosphere of a greenhouse gas considered dozens of times more potent over the short term than carbon dioxide as a heat-trapping agent. Zukoski says the West Elk Mine was the single-largest source of industrial methane pollution in Colorado from 2013 to 2015. Colorado’s first-in-the-nation rule to control methane from oil and gas development is supposed to prevent the emissions of 65,000 tons of methane a year, and in 2015, the mine vented something like 25,000 tons of methane, he said.

Zukoski notes that Arch Coal touts its West Elk Mine coal as being cleaner-burning because of its low-sulfur and high energy content.

“But the methane impacts are huge, and look what it does to the landscape. So it’s not clean,” he said.

Yet for the North Fork Valley, the economic impacts of high-paying coal mining jobs are huge. And the valley has lost many hundreds of those jobs following the closure of Oxbow’s Elk Creek Mine and Bowie Resources’ idling its mine near Paonia, leaving West Elk as the only mine still operating in the valley.

Coal’s importance to the valley was emphasized when Colorado was coming up with a state-specific version of a rule to protect roadless areas in national forests. The state rule specifically carved out a North Fork coal exemption allowing for temporary roads and methane well pads on some 20,000 acres to accommodate potential underground mining.

After a lawsuit by conservationists, a federal judge in 2014 vacated the North Fork exemption and canceled lease modifications Arch Coal obtained on two existing leases to allow for the eventual 1,700-acre expansion of its mine. The judge said the federal government failed to consider the climate-change impacts of its actions.

The Forest Service then acted to reinstate the roadless exemption after doing more environmental review, finding that the exemption could result in billions of dollars in global greenhouse gas impacts but citing the industry’s importance to the local economy. Now the Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management are again considering approving the lease modifications, and are taking comments until July 24 on a draft supplemental environmental impact statement.

Gunnison Countyweighs In

Caught somewhat in the middle of the issue is the Gunnison County Commission. The county, where the mine is located, supported the North Fork coal roadless exemption. It is now considering whether to support the lease modifications as well as a request by Arch Coal for a renewal of a royalty rate reduction — down to 5 percent, from the standard 8 percent underground rate — from the BLM.

Arch Coal spokeswoman Logan Bonacorsi explained in an email, “Given the continuing presence of less-favorable geologic conditions in certain areas of the mine and the volatile coal market environment — as evidenced by the closure of the other two mines in the North Fork Valley —` we think it is entirely appropriate to pursue this limited royalty rate relief, as allowed for under the Mineral Leasing Act for just such conditions and considerations.”

Said BLM spokesman Steven Hall, “The BLM considers royalty rate reductions as a tool to allow for the continuation of mining federal coal, which is a public resource owned by all of us. Also, the BLM considers the economic impacts to the community of closing a coal mine, both to the local community and to the U.S. The BLM also considers the very real possibility that if a mine ceased operations, the coal might never be recovered.”

John Messner, a new Gunnison County commissioner, said the county supports coal mining in the North Fork Valley and the jobs and economic benefits it provides. But before the commission is willing to support the lease modification, much less the royalty rate reduction, commissioners are asking Arch Coal to address the issue of methane venting, such as by considering the feasibility of capturing rather than venting to the atmosphere what is a valuable energy resource.

“I feel that there’s a responsibility to take action to deal with the issue of climate change. At the same time, I see it as an opportunity because the methane being released from the coal mine is an opportunity to utilize a … resource,” Messner said.

Said Gunnison Commissioner Jonathan Houck, “I kind of see that it’s a product, it’s of beneficial use. It’s not being put to its highest use now.”

In Gunnison County, he’s concerned what climate change could mean for everything from skiing to agriculture.

He said, “We’ve got climate change that’s noticeable. It’s impacting lots of different industries.”

The Crested Butte Town Council has come out against Arch Coal’s royalty rate reduction request.

A methane capture and power generation facility is operating at Oxbow, where methane production is expected to continue long after the mine shut down. But that was a result of a unique agreement that involved the Aspen Skiing Co. picking up most of the $6 million cost as a green initiative. The new environmental review on Arch Coal’s proposed lease modifications points to continuing questions about the economic feasibility of methane capture at the West Elk Mine.

Hope for Collaboration

Arch Coal officials met with Gunnison commissioners last week, and commissioners are hopeful that the company will be willing to work with the county on further considering the methane capture issue.

“I know it’s not an easy lift but I think it’s something we have to do together,” Houck said. “… I think there’s some opportunity there so I’m excited to see where we get to.”

Said Messner, “It’s an attempt to really in good faith collaboratively work with the West Elk Mine … to create a win-win partnership to move forward on these items. I’m optimistic that we can really make something happen here.”

As for the rate-reduction issue, a consideration for Messner and Houck is that some coal royalty money comes back to the state, and ultimately local communities, and that includes money going to help retrain former miners and aid local communities in transitioning to non-coal economies. A reduced royalty rate means less money for such programs.

Houck wonders whether some of what Arch Coal would save in a rate reduction could be invested in methane capture. For Messner, one question is whether there’s a role the state can play in dealing with coal methane. He noted that Gov. John Hickenlooper just issued an executive order covering a range of measures to address climate change.

In her email to The Daily Sentinel, Arch Coal’s Bonacorsi didn’t address questions related to methane capture and roadless area impacts.

Roadless for a Reason

As for Inouye — the retired biology professor, and still a researcher at the Rocky Mountain Biological Laboratory near Crested Butte — his recent hike inspired him to write the Forest Service to oppose the lease modifications. He cited concerns such as impacts to plants, habitat, and soils, and wrote that the noise, lights and methane pollution would significantly degrade the forest’s “value to native biodiversity and to hikers, campers and hunters who currently use it.”

“I urge you not to approve any proposal to allow roads into this roadless area, which has that designation for good reason,” he wrote.

For Zukoski, the visit was just one of several he has made to the area while working on the coal issue for many years.

“(Late author) Ed Abbey has a great quote about it’s not enough to fight for the land, but more important, you have to enjoy it,” Zukoski said between breaths while hiking uphill.

“It definitely fuels the fire,” he said, then added with a laugh, “to use a carbon-intensive metaphor.

“And it helps if you know the place too.”

A drilling rig associated with Arch Coal’s underground West Elk Mine operates down a hill from where it wants to expand the mine beneath a roadless area and build temporary roads.

From left, Earthjustice attorney Ted Zukoski, biologist David Inouye and Matt Reed of High Country Conservation Advocates pause where bears have left markings in an aspen forest in the Sunset Roadless Area.