The Ex-Con Coal Baron Running for Senate in West Virginia

By Tim Loh

March 19, 2018 - On a cold, rainy night in West Virginia coal country this winter, Don Blankenship glares out at a half-empty conference room at the Big Sandy Superstore Arena in Huntington. For almost an hour, the ex-coal executive and ex-con reads off a teleprompter, doing his best impression of a political candidate. For a big man, Blankenship has a surprisingly soft voice. His message is anything but. He talks of his years of union-busting, the twin evils of illegal immigration and opioid addiction—blaming the first for causing the second—and the folly of environmental regulation.

Don Blankenship, former chief executive officer of Massey Energy, speaks at a campaign event in Huntington, W. Va., on February 1.

Photo by Luke Sharrett, Bloomberg

Throughout, he never strays far from the true target of his ire: Democratic Senator Joe Manchin. Blankenship blames Manchin not only for much of what’s wrong with West Virginia, but also for helping put him behind bars.

In 2016, the former hard-charging chief executive officer of Massey Energy Co. went to federal prison for conspiring to evade safety laws in the lead-up to the worst coal mine disaster in a generation—a 2010 explosion at Upper Big Branch Mine that killed 29 miners. Manchin, the governor at the time, commissioned an independent probe that reached blistering conclusions about Blankenship’s tight grip over Massey and did a lot to seal public opinion about his role in the disaster.

Years later, as federal prosecutors zeroed in on Blankenship, Manchin, by then a senator, said on national TV that the ex-coal boss had “blood on his hands.”

During his year in prison, Blankenship maintained his innocence, even issuing a press release blaming the federal government for the explosion and referring to himself as a political prisoner. The day he got out in May 2017, he began tweeting insults at Manchin, accusing him of lying about the causes of the explosion and challenging him to a debate. Manchin said he hoped Blankenship would disappear from the public eye. Instead, Blankenship declared his candidacy for Manchin’s seat.

“Don Blankenship has entered this race because he has an ax to grind with Joe Manchin,” says Mike Caputo, Democratic minority whip of the West Virginia House of Delegates. “It’s more personal than politics.”

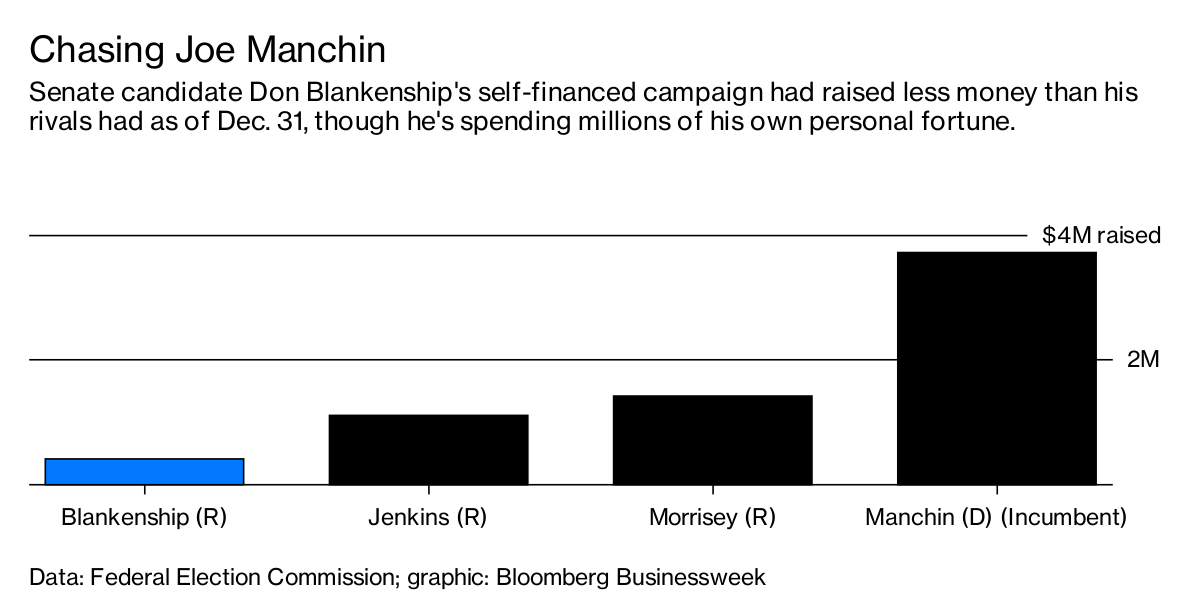

Before he can face Manchin, Blankenship has to get through the Republican primary on May ?8. His two main challengers, Evan Jenkins, the congressman who represents the state’s southern coalfields, and state Attorney General Patrick Morrisey, are more polished politicians than Blankenship. But it’s not clear that this matters. Their early polling lead has withered in the face of Blankenship barnstorming the state and spending millions of his money. A survey commissioned in early March by Jenkins shows him just two points ahead of Blankenship, who a month ago was a distant third. That’s now where Morrisey sits.

All three are trying to align themselves with the Trump agenda—a smart move in West Virginia, where Trump’s 61?percent approval rating is the highest of any state. But Blankenship can lay a truer claim to the sort of positions that got Trump elected. That’s because in many ways, Blankenship blazed the trail Trump rode to the presidency, having spent years railing against free trade and government over-reach in his role as the state’s most powerful coal executive.

To understand Blankenship’s appeal is to understand the current conservative movement in rural America, and how, in the span of several years, West Virginia became one of the reddest states in the country after decades as a Democratic enclave. Asked to describe his politics, Blankenship says simply: “I don’t believe in liberal causes because I think liberalism is too close to socialism, and that’s been proven to fail around the world.”

For generations of politicians, the key constituent force in West Virginia was the organized labor movement. No one wielded that power better than Robert Byrd, a New Deal Democrat whose 51-year tenure in the U.S. Senate is the longest ever. Today, Byrd is remembered as the masterful rainmaker who, as chair of the Senate Appropriations Committee, steered billions of federal dollars into the state, as evidenced by the scores of roads, bridges, and buildings that bear his name. After Byrd’s death in 2010, Manchin won a special election to serve out the rest of the term, and then won a full term in 2012.

By the 1980s, labor was losing its clout around the country. Blankenship, then a fast-climbing accountant at Massey, did as much as anyone to speed its decline in West Virginia. When Massey refused to sign a new union contract in 1984, it kicked off a 15-month strike by the United Mine Workers of America. Blankenship led the effort to keep Massey mines open, bringing in non-unionized workers and leading to spats of violence that left one non-union truck driver dead, and bullet holes in Blankenship’s office walls and car. Ultimately, Massey won, delivering the first of many blows to West Virginia’s union base.

Blankenship eventually became CEO and chairman of Massey. By the early 2000s, he began spending millions of his own money getting Republicans elected to state office, including $3?million in 2004 to defeat a pro-labor state Supreme Court judge. His power peaked on Labor Day 2009, when, on the top of a mountain that had been leveled for coal mining, to a crowd of tens of thousands, Blankenship delivered a broadside against his many enemies: the federal government, environmentalists, and companies that send jobs overseas. Clad in an American flag hat and shirt, he gave a performance that in hindsight seems torn from the page of a Trump stump speech, right down to the phrase “making America great” and invective against government regulation. “I know that the safety and health of coal miners is my most important job,” Blankenship said. “I don’t need Washington politicians to tell me that, and neither do you.”

Seven months later, Upper Big Branch exploded.

.jpg)

Protesters hold signs as Blankenship (front left) prepares to testify at a hearing in Washington on coal mining safety in May 2010.

Photo by Alex Wong, Getty Images

Soon, Blankenship was being hauled before Congressional committees and being held personally accountable by men he regarded as political foes. That included Robert Byrd. In a particularly heated exchange in May 2010, Byrd, then 92, sparred with Blankenship during a Senate Appropriations subcommittee hearing. “This is a clear record of blatant disregard for the welfare and safety of Massey miners,” Byrd said. “Shame!” he called out at Blankenship. It was among the last public appearances by Byrd. He was dead a month later.

Despite the deaths associated with Upper Big Branch, to a lot of West Virginians, Blankenship is more martyr than villain. Even in the state’s southern coalfields, where the disaster ruined so many lives, many miners associate him with better economic times, when the state’s coal production was three times higher than it is today. Though Massey was sold in?2011, it’s not uncommon to see people wearing old jackets and hats emblazoned with the company logo. On a February morning in Mingo County, miners coming off the overnight shift streamed into a small gas station convenience store, wearing their old Massey Energy jackets. Buying a hot sandwich before heading home to sleep, Terry Maynard, 46, acknowledges he doesn’t know how he’ll vote in November, but he isn’t ruling out his old boss. “Every coal miner I’ve talked to, you don’t ever hear Don Blankenship get blamed for Upper Big Branch,” he says.

Though he spent much of his career fighting against organized labor, Blankenship has tapped into the anger of working people in West Virginia and their deep frustration over the state’s stagnant economy. It’s consistently at the bottom in terms of job creation, along with most other measures of prosperity. In 2016, it had the country’s highest rate of drug overdose deaths, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. While these issues have long festered, the sense of exasperation has mounted in the past decade as the state’s coal production fell by nearly half, pressured by the slowdown of China’s economy and also the rise of cheap natural gas from America’s shale formations.

To feel the impact, you can zip down the Robert Byrd Freeway south of Charleston and drive to Mingo County, one of America’s poorest regions and the childhood homd of Blankenship. Near the highway exit to the town of Williamson, population 2,900, two giant signs hang from the side of a building: “LEGALIZE COAL,” says one. “TRUMP,” says the other.

While he’s popular with the base, Blankenship makes most establishment Republicans nervous, including Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, who recently said he didn’t want to see Blankenship as the GOP standard-bearer against Manchin. Blankenship’s campaign staff practically delights in how uncomfortable they make such people. “The Mitch McConnells of the world will say, ‘This is risky,’” says Greg Thomas, Blankenship’s campaign manager. “He’s been public in the past about this—Don doesn’t think Mitch McConnell should be in the Senate.”

Manchin may actually welcome Blankenship as his opponent. In an impromptu interview on Capitol Hill, Manchin chuckles when asked about Blankenship’s attempt to unseat him. “He’ll have to join a crowd,” he says. Although he’s among the most endangered Senate Democrats up for reelection—and the only West Virginia Democrat in Washington—Manchin’s prospects shouldn’t be underestimated. He’s out-raised the rest of the field, with $3.6 million by Dec. 31. Manchin is also a natural campaigner, with a gift for shaking hands, kissing babies and remembering names. Voters feel as if they know him. Manchin has been a politician for more than 35 years, going back to his time in the West Virginia House of Delegates in the early 1980s.

Over the years, Manchin has been able to morph into the kind of Democrat who can survive in a state that has gotten increasingly more red during his time in office. He’s distanced himself from the more progressive elements of the party and is culturally and politically attuned to West Virginia. In 2010, he famously ran an ad where he shot a version of Barack Obama’s cap and trade bill with a rifle. Since Trump was elected, Manchin’s been careful to focus on practical issues such as pension benefits for miners, rather than on political crusades such as immigration. That’s at times drawn the ire of his Democratic colleagues in the Senate, which could end up being a plus.

“It’s important to remember that Manchin is an incumbent, and he will be hard to beat,” says Bill Bissett, president of the Huntington Regional Chamber of Commerce. “But at the same time, this is a volatile political climate, and it’s going to be very interesting times in West Virginia.”

In recent years, Republicans took control of both branches of the state legislature for the first time since the Great Depression. The new GOP establishment is turning up the heat on Manchin. Billionaire Governor Jim Justice, himself a coal magnate from the state's southern coalfields, got elected in 2016 as a rare Democrat, then changed party affiliation last summer at a rally alongside a visiting Donald Trump. On March 14, after weeks of high-profile teacher strikes, Justice fired his Secretary of Education and the Arts—Gayle Manchin, the senator's wife.

While Justice acceded to the state's shifting political identity, Manchin is looking to tap West Virginia’s once-dependable reservoir of Democratic support. Even today, 43 percent of the state’s registered voters are Democrats, compared with just 32 percent Republicans. He may get help from such down-ticket friends as Richard Ojeda, a retired U.S. Army officer who was Manchin’s guest at President Obama’s State of the Union address in 2013. Ojeda, a state senator, is running for Jenkins’s seat in Congress and has gained a strong following, particularly as he rallied with striking West Virginia teachers. As a state senator, Ojeda has sponsored bills to legalize medical marijuana, championed Planned Parenthood, and pushed for pay raises for teachers and other public employees. In a sign of the delicate politics of West Virginia, however, Ojeda voted for Trump over Clinton in 2016. In West Virginia, even some of the staunchest Democrats voted for Trump.

When it comes to Blankenship though, Ojeda is no fan and can help in the attack should Blankenship defy the odds and become Manchin’s opponent. “Don Blankenship is a toxic leader,” Ojeda says. “He shouldn’t be allowed to run for office.”

As the primaries approach, Blankenship has continued to crisscross the state with town halls and buy up radio and TV ads, which his opponents simply aren’t doing. Bissett, of the Huntington chamber, says that by self-financing, Blankenship has freed himself from spending time, energy, and influence attending fundraisers, unlike Morrisey and Jenkins. Greg Thomas, Blankenship’s campaign manager, has a different explanation. The establishment wing of the GOP is looking for someone safe, he says, but Blankenship’s surging popularity suggests the voters want someone more aggressive. “We have to identify as the person who’s gonna take on Joe Manchin,” says Thomas. “Who in the world would get out of prison, be on probation, and run for Senate against the people who put him in jail?”

CoalZoom.com - Your Foremost Source for Coal News