Trump May Approve Strip Mining on Tennessee’s Protected Cumberland Plateau

By James Bruggers, InsideClimate News and Tyler Whetstone, Knoxville News Sentinel

February 13, 2020 - Even as the nation's demand for coal tumbles, the Trump administration is considering a permit that would allow strip mining on protected ridgelines in Tennessee's Cumberland Plateau over the objection of environmental groups and the state's Republican attorney general.

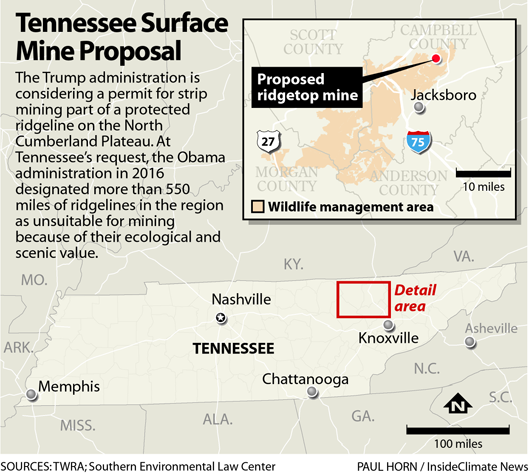

The wild, scenic terrain is within 75,000 acres designated, at the state's behest, as unsuitable for surface coal mining in 2016 by the Obama administration's Office of Surface Mining and Reclamation, the agency responsible for regulating coal mining in the state.

Senior Assistant Attorney General Elizabeth McCarter said in an October letter to the Trump administration that the federal designation prohibits surface mining on protected ridgelines in what is now the North Cumberland Wildlife Management Area, even though a mining company with mineral rights in the area had recently obtained surface rights from the state to 150 protected acres.

Triple H Coal of Jacksboro, Tennessee, has been trying to get permission to mine about 400 acres in the area since 2012, and filed an updated application last March to strip mine part of that land in Campbell County.

"I don't think the environmental impacts are there," said Phillip Boggs, an engineering consultant for Triple H, when asked about the company's plans. "They're minimal, I'll put it that way."

Michael Castle, director of the Office of Surface Mining's Knoxville Field Office, referred questions to headquarters about whether a prohibition on strip mining remains in effect on the land designated unsuitable for mining. "We are processing that permit, business as usual," he said. "There's no final decision yet."

The Cumberland Plateau spans eastern Tennessee from Alabama into Kentucky. The Nature Conservancy describes it as a "labyrinth of rocky ridges and verdant ravines dropping steeply into gorges laced with waterfalls and caves, ferns, and rhododendrons."

Coal Mining in Tennessee Is a Shadow of What it Was

This fight against Triple H Coal's mining permit pits Republicans against Republicans in a red state that President Donald Trump won in 2016 by 26 percentage points. The dispute is playing out as a nearly extinct coal industry in Tennessee yearns for a revival.

Coal mining was once booming in the mountains of Campbell County, but that was a generation or two ago—first, with miners digging coal from deep underground, and later blasting and scooping in what locals call "strip jobs."

"Fossil fuel has had its day," said Tom Chadwell, who lives with his wife, Rita, on land he inherited about three miles from the proposed new Triple H surface mine. He's the principal of a local elementary school.

Evidence of strip mining is all around, in the form of flattened land, exposed rock and streams that are "virtually dead" from repeated cycles of logging and mining. But the ridgelines that were protected in 2016 are beautiful and worth saving, he said.

"This area has given its due over and over again, in terms of deep and surface mining," he said, adding that it is time for a less damaging economy.

The push for more mining is being driven by "nostalgia," he said. "They see it as a possible path toward the riches of the past, but a lot of people never made a lot of money."

Sarah McQueen, a 37-year-old Campbell County resident and physician's assistant, said she's worried about health impacts of new mining in her community.

Studies in Kentucky and Tennessee have drawn connections between strip mining and worsening human health, including mental health.

But she said she opposes the mining proposal out of a deep sense of connection to the land she shares with others. "These mountains are a part of me, they're part of my heritage," said McQueen, a Jellico City Councilwoman. "The people of Appalachia are just a proud people and the mountains are a part of them."

Some local residents and officials, however, still see coal as part of the future, encouraged by the president's pro-coal agenda.

Campbell County Mayor E.L. Morton said coal mining generates $1 per ton in severance taxes to county coffers, and that his primary concern is about jobs. He said he can't be choosy on what industry comes to his county.

"I don't have the luxury of declining any business or jobs right now," he said.

The push to revive coal is also happening in Nashville, the state capital, with state officials looking to take back the regulatory authority over surface mining they relinquished to the federal government decades ago.

Tennessee lawmakers in 2018 passed the Primacy and Reclamation Act of Tennessee directing the Tennessee Department of Environmental and Conservation to develop a state surface mining regulatory program. That should take 12 to 15 months, said Kim Schofinski, agency spokeswoman.

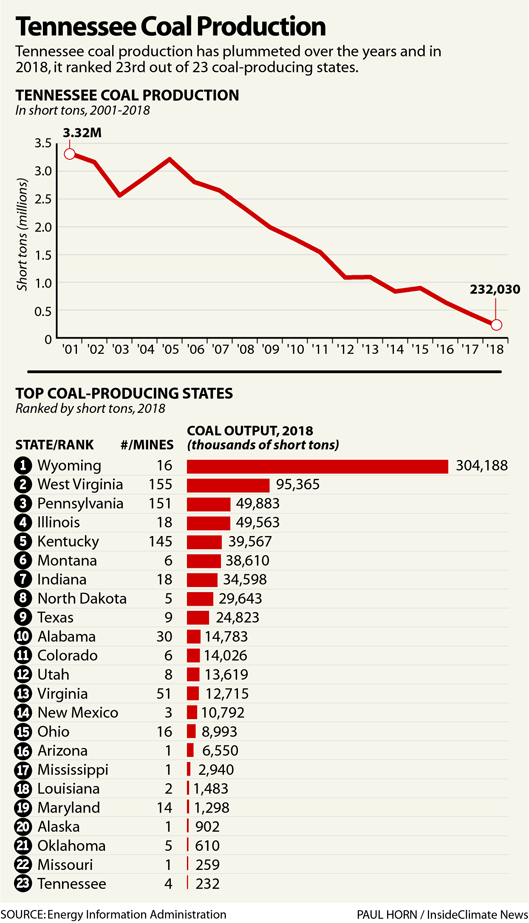

There isn't much industry left to regulate. The U.S. Energy Information Agency reports that coal mines in Tennessee produced just 232,000 tons of coal in 2018, the lowest among 23 coal-producing states, and down from 3.3 million tons in 2001. By comparison, neighboring Kentucky mines hauled out about 40 million tons in 2018, after falling from 134 million tons in 2001.

Coal-burning for electricity generation has plummeted from about 45% of the nation's generation mix to about 23% since 2010, as coal has been outcompeted by natural gas and increasingly, by wind and solar. Burning coal is also a source of greenhouse gas emissions that warm the planet.

Across the Tennessee Valley, the Tennessee Valley Authority, the nation's largest public utility, is gearing its future to natural gas, solar power and nuclear energy production.

In recent years, TVA has shut down more than half of the 59 coal-fired plants it once operated. The authority projects up to 14 gigawatts of new solar generation by 2038 alone, though how much of that gets developed could vary, depending on economic winds. By comparison, the TVA plans to operate just four coal-burning plants in 2023 with a capacity of 6 gigawatts.

Protecting the Cumberland Plateau Had Bipartisan Support

The Triple H permit application indicates it could strip mine about 150 acres of protected land. At the proposed mine, the company plans to use another coal extraction method—augering into coal seams from the side of protected ridges—that would also violate the unsuitability designation, said Amanda Garcia, a Nashville-based attorney with the Southern Environmental Law Center.

She represents the National Parks Conservation Association, Tennessee Environmental Council, Tennessee Ornithological Society, and the Sierra Club in their efforts to oppose the permit, and said the permit approval could set a precedent in the region and put at risk other protected ridges within the North Cumberland Wildlife Management Area.

Conservationists had been working for many years to protect the best of the Cumberland Plateau. In 2007, then Tennessee Gov. Phil Bredesen, a Democrat, announced the purchase of 127,000 acres of land on the northern Cumberland Plateau—property that's now managed by the state for wildlife conservation and recreation.

At the time Bredesen called it Tennessee's largest land conservation initiative since the Great Smoky Mountains National Park was dedicated in 1940, and said it would safeguard "ecologically significant woodlands on a large scale," while protecting "the natural beauty and cultural heritage that make our state uniquely Tennessee."

After six years of study, U.S. Interior Secretary Sally Jewell in 2016 announced the approval of a petition by the state to protect 75,000 of those acres. The designated area covers 600 feet on each side of a network of ridgelines that define the region's topography—some 570 miles of an elevated natural corridor in Anderson, Campbell, Morgan and Scott counties.

The Tennessee Mining Association objected to the Office of Surface Mining's decision to protect the ridgelines in 2016, and still does, said the association's president, Chuck Laine.

"To me, it's a governmental land grab," he said, describing the dispute as a "property rights issue. So obviously, the industry has been opposed to this from the beginning."

But Sen. Lamar Alexander, a Republican and former governor, praised former Interior Secretary Jewel for her decision. It would also allow existing mining operations, he noted, while making sure "these ridge top landscapes and the rivers, streams and forests that surround them can continue to bring millions of tourists and thousands of jobs to Tennessee."

The designation was the result of compromise, and it received bipartisan support. The petition Jewell approved still allows mining methods that would not disturb those ridge tops.

"The state of Tennessee asked for this area to be (protected)," Garcia said. "It's not like this was some anti-extractive industry environmental group saying, 'We want you, Obama Office of Surface Mining, to protect this land.'"

The Trump administration has generally argued that states ought to be in charge of protecting their own environment, she pointed out, and "this seems to cut against a lot of the rhetoric."

Tennessee's AG Doesn't Think a Mining Application Should Be Considered

The area has complicated land ownership that underpins the fight.

When the state purchased the land along the Cumberland Plateau in 2007, it did not buy the mineral rights, some of which are owned by Triple H Coal. Through the exercise of those rights, the company was able to acquire the surface rights to 150 acres from the state. Once acquired, it updated its request for a mining permit.

An internal email from the Trump Office of Surface Mining obtained by the Southern Environmental Law Center suggests that OSM officials agreed with the company's claim that acquisition of those surface rights gave it the ability to strip mine the area.

The office of Tennessee Attorney General Herbert H. Slatery III, arguing on behalf of Tennessee's state government, countered last fall in the letter to the OSM that under its own rules, it should not even have accepted the permit application, because the change of land ownership does not change OSM's protective designation.

The letter concludes that Triple H cannot mine "anywhere by any method" on the land it had obtained from the state. "For our part ... the (transfer) may give the company surface rights, but it does not mean the company can mine it," said Samantha Fisher, spokeswoman for the attorney general's office.

Joe Pizarchik, a lawyer from Pennsylvania who ran OSM during the Obama administration, concurred. "A change in ownership of the coal or the surface after the area is designated has no impact on the finding that the land is unsuitable for mining," he said. "Only a new petition based on new facts that were not in existence at the time of the original designation can modify the scope of the area found to be unsuitable for mining."

Pizarchik said a designation declaring lands unsuitable for mining is "relatively rare," placing the Cumberland Plateau among less than 30 areas nationally that have received such designation. Of those, he said, the Tennessee ridgelines are unique — very likely "the only ridgelines in America protected from being destroyed by coal mining."

Don Barger, a senior advisor to the National Parks Conservation Association, said there are broader implications if strip mining is allowed where the federal government had banned it. Much of the protected area in the Cumberland Plateau drains into the Big South Fork National Recreation Area, which protects the free-flowing Big South Fork of the Cumberland River and its tributaries, including many miles of scenic gorges and sandstone bluffs.

Bonnie Swinford, a Sierra Club representative in Tennessee, said she wishes Sen. Alexander would speak up loudly again as he approaches the end of his Senate career on behalf of protecting the Cumberland Plateau.

Alexander, in his third six-year term as senator, has a history of moderation with surface mining. In 2010, he called for an end to one of the most damaging forms of strip mining, called mountaintop removal. Congress never banned the practice, but at the time, he had argued that "coal is an essential part of our energy future, but it is not necessary to destroy our mountaintops and streams in order to have enough coal."

In an interview, Alexander said he still backs the 2016 federal ban on ridgetop coal mining because it means those East Tennessee landscapes "can continue to bring millions of tourists and thousands of jobs to Tennessee."

His spokeswoman, Ashton Davies, said Alexander plans to "carefully review any decision by the federal Office of Surface Mining to change that designation."