Putting Carbon Back in the Earth Re-Emerges as Bipartisan Strategy

By Laura Legere

November 2, 2020 - Pennsylvania’s fortunes have been tied for centuries to digging carbon out of the Earth in the form of oil, coal and natural gas.

If it is to remain a fossil-fuel state in a zero-carbon world, state leaders increasingly acknowledge, it will have to start putting carbon back underground.

More than a decade ago, geologists estimated more than 300 years’ worth of the state’s carbon dioxide emissions could be stored forever in various deep rock layers in Western and Central Pennsylvania. The study was followed by a burst of research on the potential for carbon capture, use and storage in Pennsylvania prompted by a 2008 state law.

Now the suite of clean-energy technologies is again emerging as a focus, as scientists emphasize that human-caused CO2 emissions must fall to net-zero by 2050 to keep warming below 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels. The only way to keep burning fossil fuels in that scenario is to capture the carbon dioxide that would otherwise waft from the stacks at power plants, steel mills and petrochemical factories.

Coal, oil and gas companies — and their workers — increasingly see it as a question of their industries’ survival.

“There is a growing acknowledgment among many circles that [carbon capture, utilization and storage] will need to be part of our global climate strategy,” Denise Brinley, executive director of Pennsylvania's Office of Energy, said.

“Now that the momentum seems to be picking up, why wouldn't Pennsylvania be at the table for helping to address serious climate issues through technology and innovation?”

The Wolf administration recently announced a partnership with six other states to share strategies for transporting carbon dioxide from industrial sites to future injection sites.

The state’s economic development, environmental protection and conservation agencies all began collaborating last fall to resolve technical, regulatory, economic and policy issues that have been obstacles to advancing carbon capture.

Some state legislators along with labor and environmental groups see an opportunity in Pennsylvania’s alternative energy law, whose targets will plateau next year after 17 years of gradually increasing clean energy purchases.

They are pushing to revive the program in 2021 by requiring utilities such as Duquesne Light and West Penn Power to get a growing share of their electricity not just from renewable sources, like wind and solar, but also from zero-emitting sources like nuclear plants and from coal or gas power plants outfitted with technology to capture their carbon emissions.

Even Gov. Tom Wolf’s effort to join the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative, which would require Pennsylvania power plants to start paying for their carbon emissions, could jump-start the state’s investment in carbon capture. State regulators are exploring using some of the expected $300 million in annual proceeds from that program on carbon capture research and development.

‘Fossil Fuels Are Here to Stay’

The world’s dominant strategy to cut down on greenhouse gas emissions is to use energy more efficiently and switch rapidly to cleaner sources.

Another, less established tool is to capture the carbon dioxide put out by factories and power plants instead of sending it into the atmosphere.

Carbon dioxide is separated from other gases in the facilities’ exhaust streams using chemical solvents, compressed and shipped, usually by pipeline, to where it can be used or injected underground.

The technology is not new: One of the world’s largest carbon capture projects began operating in the late 1980s at a natural gas processing plant in Wyoming where carbon dioxide is an impurity that must be filtered out. A coal-fired power plant that opened in 2000 in western Maryland captures a fraction of its carbon emissions for use in food products, like carbonated drinks.

.jpg)

The captured gas can also be used to coax more oil and gas out of the ground, and then sealed off permanently in porous rock deep underground.

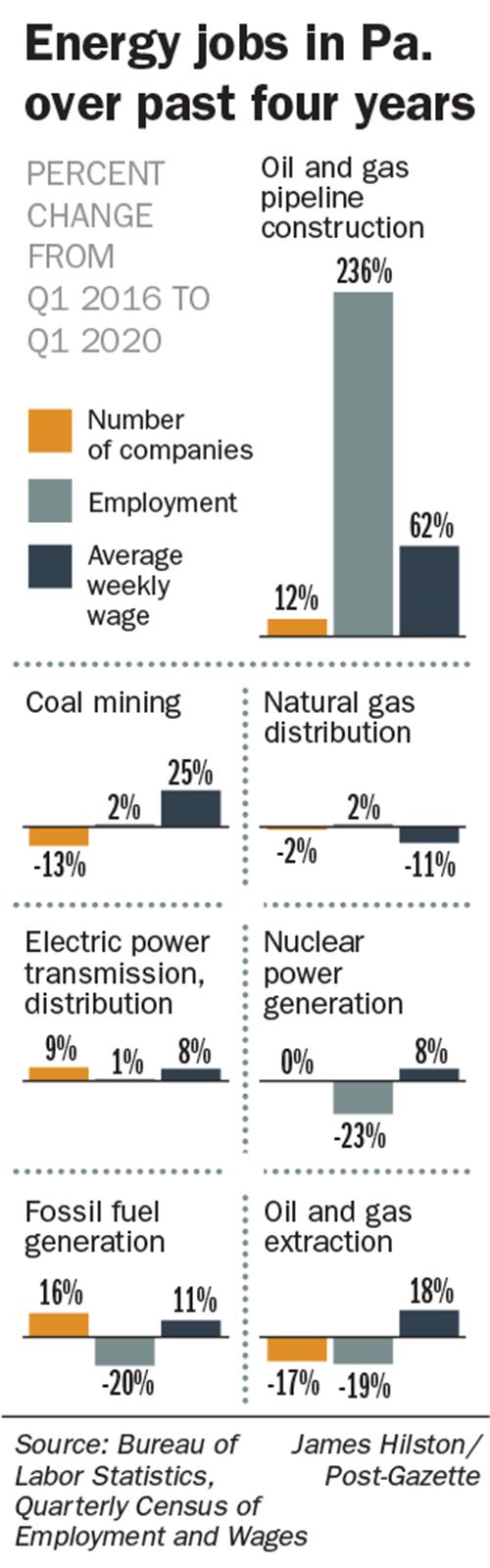

Companies that build, operate and upgrade fossil fuel power plants — and the trade unions that do the work — have embraced carbon capture as a way to preserve jobs and create new ones.

Installing pollution control equipment takes a lot of well-paid labor.

The Carbon Capture Coalition — whose 80 members include the energy companies Shell and Baker Hughes, the manufacturer AK Steel, the United Mine Workers of America and other unions, and environmental groups such as The Nature Conservancy — estimates that each typical retrofit of a steel mill or a coal- or gas-fired power plant would create between 1,100 and 3,300 construction jobs.

That makes supporting carbon capture an attractive political position, regardless of party.

Democratic presidential candidate Joe Biden’s $2 trillion climate plan calls for accelerating the development and deployment of carbon capture and storage technology through enhanced tax incentives and research funding.

President Donald Trump, a Republican, signed a broad federal funding bill in 2018 that more than doubled the value of tax credits for carbon storage projects — a move seen as a key step in making more projects economically viable.

While dismantling climate regulations has been a hallmark of the Trump administration, carbon capture fits with its broader effort to boost fossil fuels.

“Fossil fuels are here to stay. They are not going to be a transition fuel,” said Lou Hrkman, deputy assistant secretary for clean coal and carbon management at the U.S. Department of Energy, during a webinar in June on opportunities for carbon capture and storage in Pennsylvania.

“Pennsylvania really has the opportunity to lead in this area.”

‘Unmet Expectations’

Pennsylvania does seem like a logical place for carbon capture to work:

• Its power sector releases more CO2 annually than all but three other states.

• Heavy industries, such as cement and steel, are generally located near underground reservoirs that are a good fit for storage.

• It has a mature oil and gas industry that could buy CO2 and use the gas to coax more fuel from wells.

• It has an established fossil fuel workforce adept at securing mineral leases, drilling wells and building pipelines.

Still, there are already 13 commercial-scale carbon capture facilities operating in the U.S. and another 30 projects under development, according to the Carbon Capture Coalition. None of them are in Pennsylvania.

Ms. Brinley said she is aware of at least one prospective manufacturing project in the state that intends to incorporate carbon capture and use it as a component of its business model, but it is not its main purpose.

“I do think demonstration projects are important,” she said. “We just are not at that level yet.”

Carbon capture, use and storage technologies, or CCUS, are controversial because of concerns about their economic viability or they are seen as prolonging the use of oil, coal and gas.

Texas’ Petra Nova, the U.S.’s only large-scale carbon capture retrofit of an existing coal-fired power plant, suspended its CO2 capture operations in May. Low oil prices made it uneconomical to keep capturing and pumping the gas underground to produce more oil.

The International Energy Agency, which sees carbon capture technologies as crucial in the world’s clean energy transition, began a report in September with the line, “The story of CCUS has largely been one of unmet expectations.”

Kristin Carter, assistant state geologist of the Pennsylvania Geological Survey who has been leading the state’s efforts, said some heavy industries, like cement, unavoidably release carbon dioxide in the manufacturing process, so the only way to reduce their emissions is to capture it.

“Even if we move away from fossil fuel sources for our energy use, that's not going to get us all the way there. We have to solve the problem because there are other industries that cannot decarbonize just by switching fuels.”

While the carbon capture conversation quieted for a while in Pennsylvania, there was never a lull in the technical research, she said.

The Pennsylvania Geological Survey has spent the past decade working to define the carbon storage potential in different regions and geological layers of Pennsylvania and participating in regional partnerships that have piloted carbon storage projects in other states.

A 2005 study estimated that Pennsylvania has the geological capacity to store about 88.5 billion metric tons of carbon dioxide.

But what matters more for planning capture and storage projects is defining and securing capacity in specific zones underground. The survey has identified geologic pools and — crucially — stacked underground horizons that might each accommodate carbon injections.

Some states have extensive, porous rock formations “that can just take and take and take CO2,” Ms. Carter said. Pennsylvania’s storage potential, especially in the southwest, includes layers with different capacities at different depths.

To complicate things, there are already “so many things going on” underground here: historical and current coal, oil and gas extraction, natural gas storage fields and the potential to store natural gas liquids.

“That coordination of subsurface resources is a big deal,” she said.

New Collaborations

As researchers get a clearer picture of the geological prospects for storage, the state is starting to turn to the thorny issues above ground. “Considering this infrastructure piece is really the next logical step,” Ms. Carter said.

A decade of infrastructure buildout associated with massive new natural gas production from the Marcellus and Utica shales has shown that pipelines are contentious and Pennsylvania’s terrain can be unaccommodating.

“It's not because it's easy. It's because it would be necessary,” Ms. Carter said.

Carbon capture proponents say the most economical way to spur large-scale adoption of the technology is to establish shared carbon dioxide pipeline and storage infrastructure around hubs of industry.

The multistate collaboration on carbon transportation infrastructure will help Pennsylvania apply lessons from other states’ experiences. One of the partners, Wyoming, is pursuing an extensive CO2 pipeline network.

At the same time, Ms. Carter hopes companies will use the state’s interagency workgroup as a resource to explore how carbon dioxide storage or use in Pennsylvania might become part of their business model.

She sees promise in a new 20-state collaboration called the Midwest Regional Carbon Initiative, which is an offshoot of the decades of cooperative work the Pennsylvania Geological Survey has done with regional states.

Last time, Michigan landed the big demonstration project.

“If I have anything to say about it,” Pennsylvania will secure one or more projects through the new initiative or from connections she forms there, she said. “That’s my goal.”