Wielding a Deciding Vote in Senate, Joe Manchin Brings Appalachian Energy to Climate Debate

By Daniel Moore

February 15, 2021 - Joe Manchin knows how it may appear to climate advocates: a West Virginia senator and incoming chair of the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee teaming up with a Wyoming Republican senator to advance energy goals while together they represent the top coal-producing states in the country.

But Mr. Manchin, Appalachia’s loud and proud native son on Capitol Hill, insists it is possible to both advocate for the fossil fuel industry and achieve net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050, the top-line U.S. goal for President Joe Biden and congressional Democrats.

Mr. Manchin’s views on energy and climate — and, more broadly, on the direction of the country as it emerges from a global pandemic and economic crisis — will be front and center on the national stage in this session of Congress.

A 73-year-old conservative Democrat and former West Virginia governor, Mr. Manchin wields the potentially deciding vote in an evenly split Senate under the Democrats’ control. With Democrats needing his support, Mr. Manchin’s views — and those of West Virginians and the broader Appalachian region — will factor into the legislative process every step of the way, a position of remarkable political influence for a senator outside of party leadership.

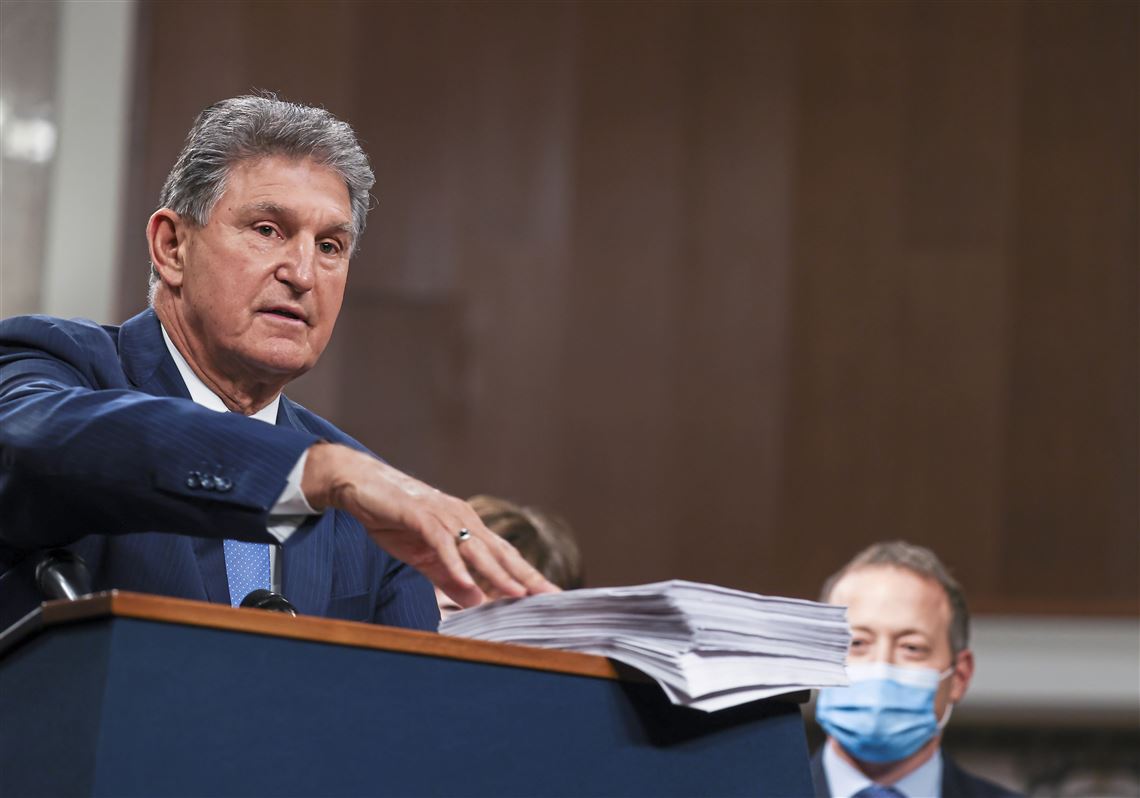

Joe Manchin

Mr. Manchin did not respond to Post-Gazette requests for an interview. But he has been prominent lately in national news reports, trade publications and West Virginia radio airwaves, offering his characteristically blunt assessments of the next Congress.

He has made it clear that he intends to return the country to a bipartisan, centrist and incremental approach to governing at a time of deep polarization, political party tribalism and rising demands to go big on the most complex problems facing the nation.

Less than a month into Mr. Biden’s term, Mr. Manchin has been a thorn in the Democrats’ side, suggesting there could be internal clashes as the party tackles pressing issues after winning control of Congress for the first time in a decade.

Mr. Manchin has objected to key parts of Mr. Biden’s $1.9 trillion COVID-19 relief plan, including $1,400 direct payments and a minimum wage hike to $15 an hour. He voiced opposition to the fast-track process that would allow Democrats to move forward with no Republican votes (though he ultimately voted to start the process this month), and does not support ending the Senate’s filibuster, which has been a target for many Democrats.

And as Democrats see an infrastructure bill that addresses climate change as a top priority this year, Mr. Manchin’s position will present an opportunity, or a roadblock, to advance a large-scale plan.

Success in a Red State

This is in some ways a culminating moment for Mr. Manchin.

He was born in the coal town of Farmington, about 30 miles southwest of Morgantown, and raised by parents of Italian and Czechoslovakian descent. His father and grandfather were small-business owners and both served as Farmington mayor. While Mr. Manchin was away at West Virginia University, his hometown was the site of the 1968 Farmington Mine Disaster, an explosion that killed 78 miners, including his uncle, and helped to spur a landmark federal health and safety law for coal miners.

After working for his family’s business, Mr. Manchin won a seat in the West Virginia General Assembly at age 35. He began a climb that led, in 2004, to a landslide victory in the governor’s race. Mr. Manchin’s success became more remarkable as the Mountain State, a historically Democratic stronghold, turned Republican in a matter of a couple of decades.

In November 2010, he won a special election to fill the seat left by the death of Democratic Sen. Robert Byrd, who had represented West Virginia in the upper chamber for 51 years. Two years later, he won a full six-year term with more than 60% of the vote — the same year 62% of West Virginians voted for Republican Mitt Romney for president.

In 2016, Donald Trump won West Virginia by 41 percentage points, a greater margin of victory than in any other state, and he won by 39 points in 2020. In between those two elections, Mr. Manchin managed to win another Senate term in 2018 by 3 percentage points.

Mr. Manchin has navigated perhaps the toughest landscape of any Democrat in America with a centrist agenda. He consistently ranks as the most conservative Democrat in the Senate, according to an analysis of his congressional legislative record by VoteView.

He is also the consummate politician, according to people who have followed his career. He’s a shrewd back-room negotiator at the center of bipartisan talks in Washington and knows how to work a room at constituent events back in West Virginia.

“People trust Joe Manchin,” said James Van Nostrand, a law professor and director of the Center for Energy and Sustainable Development at West Virginia University. “He knows everybody, and everybody knows him. It’s a small state.”

Taking Care of West Virginia

Mr. Manchin could be seen as channeling Mr. Byrd, who spent much of his tenure at the upper echelons of Senate leadership and was prolific at bringing benefits to his state.

Mr. Byrd was responsible for so many roads, bridges, schools, hospitals, research laboratories, federal buildings and visitor centers scattered across the state that fiscal watchdog groups referred to them as “Byrd droppings.”

Mr. Byrd was also known for his knowledge of the arcane rules of the Senate, defending its traditions, like the filibuster, designed to protect the rights of the minority party.

Mr. Manchin recently recalled a conversation with Mr. Byrd about why he fought for the eponymous Byrd Rule, which blocks provisions deemed to be “extraneous” to a fast-tracked bill’s basic purpose of implementing budget changes. The Byrd Rule could sink Democrats’ efforts to raise the minimum wage in the COVID-19 relief bill, should it be found not to have a big enough budgetary impact.

“If they think they want to just jam things down people’s throats — no. There’s a process,” Mr. Manchin said during a virtual forum this month hosted by the Bipartisan Policy Center. “I’m not going down that path and destroy this place. I’m not going to let the Byrd Rule be decimated. I’m not.”

West Virginians are “used to having their politicians, when they’re in key positions, to be taking care of us,” said Mr. Van Nostrand, who is working on a book about lost opportunities in clean energy investment in West Virginia.

‘I’m Not Changing’

As energy committee chair, Mr. Manchin will face pressure from climate advocates to advance policies in line with Mr. Biden’s goal of net-zero power sector emissions by 2035.

They have argued carbon capture technology is unrealistic and the country needs to make a plan principally focused on a gradual phase out of fossil fuels.

“We’re way behind where we need to be in terms of hitting emission reduction goals,” said Grant Carlisle, senior policy adviser for the National Resources Defense Council’s climate and clean energy program.

A key proposal expected to come before Mr. Manchin’s committee is a Clean Energy Standard to set limits on emissions from different sources of energy. Mr. Carlisle called it a “once-in-a-generation opportunity” to get to emissions reductions by 2035.

Mr. Manchin’s view that federal government overreach has amounted to a “war on coal” could complicate negotiations and align him more with the committee’s top Republican, John Barasso of Wyoming.

In a 2010 Senate campaign ad, Mr. Manchin boasted about suing the Obama administration for alleged “attempts to destroy the coal mining industry” and shot a hole through the cap-and-trade bill, which would have capped carbon emissions and allowed companies to trade credits. “It’s bad for West Virginia,” he said in the ad.

His first actions as a senator included support for legislation to curb the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s powers to regulate greenhouse gases and to mandate cuts in mercury pollution as a condition of receiving permits for new mines.

This year, Mr. Manchin criticized Mr. Biden’s cancellation of the Keystone XL oil pipeline and his moratorium on new federal leasing of oil and gas drilling. The senator has instead thrown his support behind carbon capture technology and innovations that he believes can keep coal, oil and natural gas part of America’s “all-of-the-above” energy mix, alongside nuclear, hydropower, solar, and wind energy.

Last week, he wrote letters to Mr. Biden, asking the president to reverse his Keystone XL decision and touting the benefits of natural gas drilling and pipelines, including the Mountain Valley Pipeline project designed to carry natural gas from West Virginia to Virginia.

To ban fossil fuels, advocates would have to “try to remove me or throw me out,” he told a West Virginia radio station last month. “Because I’m not changing. Common sense is common sense.”

Proponents of a carbon tax, he said during the virtual forum this month, can “forget it, as long as I’m here and there’s 50 [Democratic votes in the Senate], and it takes 51 to pass it.” He added, “If they want to have a conversation [about] how we improve our climate and do it in a most responsible way, then, yeah, they’d have me in a heartbeat.”

Such talk “plays extremely well here,” said John C. Kilwein, a political science professor at West Virginia University, even if it is out of step with most Democrats across the country.

“If you didn’t have Joe Manchin, I can’t think of a statewide candidate who’s a Democrat who could win,” Mr. Kilwein said. Calls for a progressive primary challenge in 2024 are “psychotically unrealistic” and would be “a complete waste of money.”

“Joe Manchin’s a survivor,” he said.

Innovation as the Answer

Mr. Manchin has pointed to his recent accomplishments as the top Democrat on the energy committee working with Republican chair Sen. Lisa Murkowski of Alaska. During the virtual forum this month, Mr. Manchin joked that “there’s no one going to be comfortable thinking a senator from Alaska and a senator for West Virginia are in charge of energy and they’re going to protect the climate.”

“I can understand that because they just didn’t know who we were,” Mr. Manchin said.

And yet, last year, the committee shepherded into law both the Great American Outdoors Act, the most significant land conservation legislation in 50 years, and the Energy Act, the first major update to U.S. energy policy since 2007. The latter bill included $447 million for carbon removal research and development.

Going forward with Mr. Barasso, Mr. Manchin favors tax credits that can incentivize clean energy growth and funding boosts to the National Energy Technology Laboratory’s fossil fuel research program, based in facilities in Morgantown and in Pittsburgh’s South Hills.

Utilities upgraded their plants to capture sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxides in the 1990s, Mr. Manchin pointed out, and next generation f American-made pollution control technology could be exported to countries like China and India.

“Fossil fuels aren’t going anywhere anytime soon, particularly in countries that are seeking to expand access to electricity,” Mr. Manchin said during a hearing Feb. 3 he convened on climate change.

An aide on the energy committee said it can set policies that encourage “technological paths for fossil fuel use that are clean” alongside other forms of energy while prioritizing the prevention of regional economic pain that comes with shutting down plants without simultaneous reinvestment and new job creation.

At electric utilities across the country, “there’s movement toward emissions reduction goals” the staffer said. “It may not be the 2035 goal the administration has put out there, but it’s at least an acknowledgment that there’s increasing ability to tackle this issue.”

“The senator is taking a much more realistic stance on fossil fuels and is supportive of more of a common-sense approach to progress,” said Stephen Nelson, CEO of Longview Power, which operates a coal-fired power plant just north of Morgantown and plans to add natural gas and solar facilities.

“There really does need to be a balance between improving the environmental performance without needlessly gutting good-paying jobs and casting higher costs and less reliable electric supply on the public,” Mr. Nelson said.

Mr. Nelson said no one in the industry denies climate change is a serious issue. But renewable energy mandates that move too quickly would harm the economy and energy prices, he said.

Mr. Manchin has toured the company’s plant and “has always answered our phone calls,” Mr. Nelson said. “He’s got leverage, which is great, and I expect that we’ll be able to get his ear.”